Family Law Litigation in Supreme Court

|

|

This page from JP Boyd on Family Law and others highlighted in orange explain trial procedure and litigation in BC family law. They are under editorial review to provide more thorough, current, and practical guidance. Since 2020, procedures, forms, and laws have changed significantly. While gross inaccuracies have been corrected, some details may still be outdated. These pages were not included in the 2024 print edition. |

The Resolving Family Law Problems out of Court chapter tells you about your various options you have for resolving your family law dispute without having to go to court, including collaborative negotiation, mediation, arbitration.

If you have decided to start a court action, the general chapter on Resolving Family Law Problems in Court provides an overview of the two courts (BC Provincial Court or BC Supreme Court). That chapter explains which court is appropriate for specific kinds of family law dispute, and the pros and cons of each court. Deciding which court to start your action in is an important decision because once you have started in one court, you may not be able to move your family law action to the other court.

If you have decided to start in the BC Supreme Court, or if the other side has already started an action there, this chapter explains what the overall process looks like, from start to finish.

A few definitions

Before going further, it'll help to learn some of the terminology used in family law litigation. (You can also find more definitions in the Common Legal Words and Phrases part of this resource.)

- Family law action: In general a family law action is type of civil action (i.e. it's not a criminal case), and is started by a person (or persons) seeking to resolve a family law dispute. A family law action can still include other civil claims related to that family law dispute, but the BC Supreme Court treats family law actions differently from general civil actions. A specific set of procedural rules (called the Supreme Court Family Rules) are applied, the forms are unique, and the court records are not as open to the public.

- Claimant: The person who starts a court action in the Supreme Court is the claimant. There can be more than one claimant, but we will use the singular for simplicity.

- Respondent: The person against whom a court action is brought is called the respondent. There can be more than one respondent, but we will use the singular for simplicity.

- Parties: The claimant and the respondent are, together, called the parties to the court action (no matter how many actual claimants or respondents there might are).

- Claim: A claimant who wants to start a court action in the BC Supreme Court files a Notice of Family Claim in that court. In some very specific circumstances, the claimant needs to file a Petition to the Court or a Requisition to start their court action instead of a Notice of Family Claim. In this section, "claim" refers to all of these documents (Notice of Family Claim, Petition to the Court, or Requisition). The claim usually includes a summary of the relevant facts alleged by the claimant, the laws the claimant says are relevant, and the claimant's list of the orders they want the court to make.

- Reply: A respondent who objects to all or some of the orders sought by a claimant in the BC Supreme Court will file a Response to Family Claim (if they were served with a Notice of Family Claim) or a Response to Petition (if they were served with a Petition to the Court). In this chapter, reply refers to either of these documents (Response to Family Claim, or Response to Petition). In their reply, the respondent states if they agree or disagree with (some or all of) the facts alleged by the claimant, and if they agree or disagree with (some or all of) the orders the claimant is asking for.

- Counterclaim: A respondent can give the court their own list of orders they want the court to make. In order to do this, they file a Counterclaim in addition to their Response to Family Claim (for claims started by a Notice of Family Claim). If they were served with a Petition to Court, the respondent will need to apply to court to convert the claim from a petition-based proceeding into a full action (typically the Petition to Court would then be deemed to be a Notice of Family Claim, and the respondent could then file a Response to Family Claim in addition to a Counterclaim). A counterclaim is similar to a claim: it provides a summary of the relevant facts of the family law action, the laws the respondent says are relevant, and the respondent’s wish list of the orders the respondent will want the court to make in the court action.

- Response to Counterclaim: A claimant who objects to all or some of the orders listed in a respondent's counterclaim will file a Response to Counterclaim. This document is also a reply. In the Response to Counterclaim, the claimant states if they agree or disagree with (some or all of) the facts contained in the counterclaim, and if they agree or disagree with (some or all of) the orders the respondent is asking for.

- Pleadings: The documents that a claimant and a respondent file in BC Supreme Court to start or reply to a BC Supreme Court action are called pleadings. In most BC Supreme Court family law actions, the pleadings are the Notice of Family Claim, the Response to Family Claim, Counterclaim, and Response to Counterclaim.

- Judicial Case Conference (or JCC): In most cases this is the first court appearance where the parties must attend. A JCC happens early on, takes about an hour and a half, and is a somewhat informal process. The parties and their lawyers (if they have them) sit down at a table with a judge to discuss a possible resolution of some or all of the claims and counterclaims. A JCC is like a mini mediation. The judge cannot make any orders (other than some procedural orders) unless the parties agree, and what is discussed is confidential and cannot be used outside of the JCC proceedings.

- Interim Application: An interim application is an application that a claimant or respondent brings to court, when they want the court to make a temporary (interim) order. Interim applications are made after the court action has been started and the parties attended the JCC, and before trial. A party can apply for an order that allows them to bring their interim application before the JCC is held. Interim applications can be made by filing a Notice of Application, or a Requisition (not the same Requisition as the one that starts a BC Supreme Court action).

- Affidavit: A legal document in which a person provides evidence of certain facts and events in writing. Affidavits are important in interim applications and summary trials because written testimony is generally the only form of evidence that the BC Supreme Court will accept from parties and witnesses outside of a proper trial setting. The person making the affidavit (called the deponent) must confirm that the statements made in the affidavit are true, and they must be signed in front of a commissioner for taking oaths (usually a lawyer, a notary public, or a court official) who takes the oath or affirmation of the deponent. Affidavits are used as evidence, and as a substitute for having the person make the statements in court before a judge. An affidavit often includes documents (that are attached to the affidavit as exhibits) to support the facts stated in the affidavit. For example, if the deponent says that they received a text message from one of the parties stating their plan to move to Alberta, a printed copy of the text message can be printed and attached to the affidavit as an exhibit. Depending on the type of interim application a party brings, they will usually need to file an affidavit together with their application.

- Financial statement: A financial statement is much like an affidavit, but is specifically tailored to provide financial information about the party who swears or affirms it. It has its own form under the Supreme Court Family Rules, and a party in a family law action that involves child support, spousal support, the division of property, or the division of debt will need to prepare a financial statement that describes their income, expenses, assets, and liabilities.

- Trial: The court makes its final decision about the orders the parties request in their claim and counterclaim at trial. A trial is a formal hearing where the parties and their lawyers (if they have them), appear before a judge and present their evidence by calling on live witnesses to give testimony. The parties or their lawyers provide their argument (submissions) which tells the court why it should make the orders listed in their claim or counterclaim. A summary trial is the same as a trial except that the evidence from parties and their witnesses is given by affidavit, as opposed to each person appearing in-person to tell the court their evidence. A summary trial can resolve some or all of the orders the parties are asking for in their claim or counterclaim. The section on Trials and Supreme Court Family Law Proceedings provides more information about the differences between trials and summary trials. For simplicity, when we use the term trial, we refer to both summary trials and traditional trials.

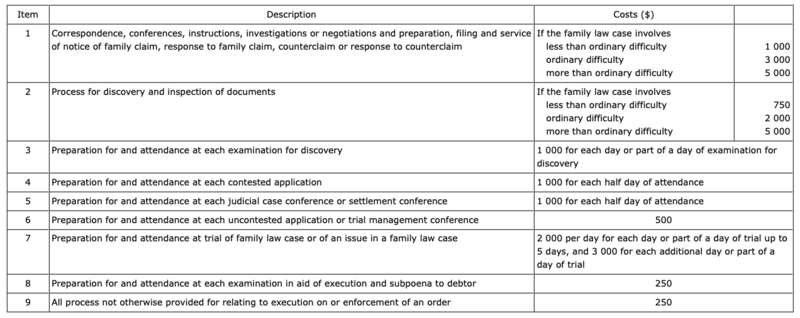

- Costs: This has a specific meaning in BC Supreme Court and in the Supreme Court Family Rules. Costs refers to what the unsuccessful party must pay the successful party, and they are often sorted out after the litigation has ended, either by agreement between parties, or in special hearings before a Registrar that are conducted after other orders are decided. Costs are rarely equal to what parties spend on legal fees and other expenses. While costs are based on the tariffs set by the BC Supreme Court Family Rules, judges retain a lot of discretion to decide which party is responsible for paying them, how high or low the calculation of costs should be set within the ranges allowable, and whether to use costs as a mechanism to discourage a party's unreasonable behaviour.

- Judge: In the BC Supreme Court there are different a few different judicial roles. A full Justice of the court has the power to hear and decide any type of claim under any kind of procedure, from interim applications to full trials. An Associate Judge can hear and decide on interim applications (where interim and procedural orders are made) but they cannot preside at trial or issue a final judgment. A Registrar can preside over only limited and specific types of hearings (e.g. hearings to settle costs). The kind of judge that can hear your application depends on the orders you are asking the court to make. In this section judge is used to refer to all types of judges.

The court process in a nutshell

The sections in this chapter deal with the stages of family law litigation in BC Supreme Court in the order that most parties will typically experience them. The process and its stages are summarized below, and this summary reflects the structure of the sections that follow in this chapter. Be sure to reference the definitions above, as these terms are used in the descriptions below.

The claimant starts the court action

The claimant starts a BC Supreme Court action by initiating pleadings at one of the court's registries. This is done by filing a claim at the registry. Once the action is filed at one registry, all further court documents must be filed at the same registry unless there is a court order transferring the court action to another registry. Once the claim is filed, the claimant must serve a copy on the respondent. Serving the filed claim involves having it hand-delivered to the respondent by someone other than the claimant. Remember that the claim only lists the claimant’s wish list: it is not an actual court order. It is up to the judge to decide, at an interim application or at trial whether the orders that the claimant asks for in their claim will be granted.

The respondent files their reply

The respondent has a certain amount of time after being served with the claim to respond to the court proceeding by filing their reply and, if applicable, their counterclaim. The number of days that the respondent has to file their reply is set out in the claim they were served with. The respondent must deliver their reply and any counterclaim to the claimant at the claimant's address for service, which will have been listed in the claim. Remember that a respondent's counterclaim, just like the claimant's claim, is only a list of the orders that the respondent wants. It is not an actual court order. It is up to the judge to decide, at an interim application or at trial whether the orders that the respondent asks for in their counterclaim will be granted.

If the respondent does not file a reply the claimant must file an affidavit of personal service. The affidavit of personal service is sworn or affirmed by the person who hand-delivered the claim to the respondent (i.e. not the claimant themself). If the service period as stated in the claim has run out and the respondent has not filed a reply, the claimant could obtain orders without the respondent's knowledge or participation.

The claimant files their reply to any counterclaim

If the respondent filed and served a counterclaim, the claimant has a fixed amount of time after receiving it to file their response to the counterclaim. The claimant must deliver their filed response to counterclaim to the respondent's address for service, which will be listed in the reply and counterclaim.

Generally speaking, now that parties have filed, delivered, and received each other's claim, counterclaim, and replies, the pleadings is concluded.

The parties exchange documentation

Next, he parties gather the documents that that are relevant to the orders either party is asking for, whether those documents help or hurt their case. What matters is that the documents are relevant to any of the orders requested in the claim or counterclaim. Here are a few examples:

- If the claim is asking for orders to divide property, the respondent has to gather banking and investment statements even if their counterclaim did not ask for an order to divide property.

- If the counterclaim is asking that the claimant pay child support, the claimant has to gather income documentation and file and serve on the respondent a financial statement even if the claim is only asking for parenting orders and does not include a request for child support.

- If the counterclaim is asking only for parenting orders, the claimant has to provide relevant documentation about the children even if their claim did not request any parenting orders.

they need to explain why they should have the orders they are asking for. Because trials are not run like an ambush, the parties must exchange their information and documents well ahead of trial. This way everyone knows exactly what is going on and how strong each person’s case is. There are different processes in Supreme Court and Provincial Court for exchanging information. For more details, see the section Starting a Court Proceeding in a Family Matter in this chapter.

The parties attend case conferences. Case conferences are meetings with judge to talk about the court proceeding. They often provide an opportunity to talk about settlement option and to ask for orders about steps in the court proceeding as the proceeding heads to trial. For more about case conferences, see the section about Case Conferences in this chapter.

Each party answers questions out of court. In court proceedings before the Supreme Court, each party is usually required to attend an examination for discovery. This is an opportunity for each party to ask the other parties questions about things that are relevant to the legal issues so that everyone knows the evidence that will be given at the trial. This is also an opportunity to ask each party to provide more documents.

Go to trial. Assuming that settlement isn't possible, court proceedings are resolved by trials. At trial, each of the parties presents their evidence and explains to the judge why the judge should make the orders they're asking for. The judge may make a decision resolving the decision on the spot; most often, however, the judge will want to think about the evidence and the parties' arguments and will give a written decision later, often weeks or even months later.

Remember that you can continue to try to negotiate a settlement with the other party at every stage of this process. You can even decide to try mediation in the middle of a court proceeding, and, if you are getting tired of the court process or are worried about how long it will take to have a trial, you can abandon the court process altogether and go to arbitration.

While working your way through the court process, you may find that it's sometimes necessary to ask for interim orders. These are temporary orders that address a short-term problem or need, or that help the court proceeding get to trial. In family law cases, people often ask for interim orders to protect someone when family violence is an issue, to deal with the payment of child support or spousal support, to get a parenting schedule in place, to determine how the children will be cared for, or to protect property while waiting for the trial.

The process for interim orders is a miniature version of the larger process for getting a claim to trial.

The applicant starts the application. The person who wants the interim order, the applicant, starts the application process by filing an application and an affidavit in court, and delivering the filed application and affidavit on the other party, called the application respondent. The application describes the orders the applicant wants the court to make. The affidavit describes the facts that are relevant to the application and the orders the applicant is looking for. For more information about affidavits, see the page, How Do I Prepare an Affidavit?, in the Helpful Guides & Common Questions part of this resource.

The application respondent files a response. The application respondent, the person who is responding to the application, has a certain amount of time after receiving the application and affidavit to file a response and an affidavit in court. The response says which orders the person agrees to and which they object to. The affidavit describes any additional facts that are important to the application. The response and affidavit must be delivered to the applicant.

The applicant may file another affidavit. The applicant has a certain amount of time after receiving the application respondent's materials to file another affidavit in court. This affidavit is a response to the application respondent's affidavit and describes any additional facts that are important to the application. This affidavit must be delivered to the application respondent.

Go to the hearing. Assuming that settlement isn't possible, the only way to resolve the application is to have a hearing. At the hearing, each of the parties will present the evidence set out in their affidavits and explain to the judge why the judge should, or shouldn't, make the orders asked for. Most of the time the judge will make a decision resolving the decision on the spot; sometimes, however, the judge will want to think about the evidence and the parties' arguments, and will give a written decision later.

For more details see the section Interim Applications in this chapter.

There are lots of details we've skipped over in this brief overview, including details about important things like experts, case conferences, and the rules of evidence, but this is the basic process in a nutshell. These other details are governed by each court's set of rules. The rules of court are very important, and the rules of the Provincial Court are very different than the rules of the Supreme Court.

You can probably guess that getting a court proceeding to trial can be a long and involved process, and that if you have a lawyer representing you, it'll cost a lot of money to wrap everything up. Making these procedural delays worse, trial dates are often in short supply. In Vancouver, for example, you may not be able to get dates for a one-week trial any sooner than 18 months.

It's important to remember that you and the other party can agree to resolve your dispute out of court at any time in this process. If you haven't done so already, please read the chapter Resolving Family Law Problems out of Court.

Rules promoting settlement

Just because a court proceeding has started, it doesn’t mean you will be going to court. The majority of cases settle prior to trial; in fact, the number of civil court proceedings in the Supreme Court of British Columbia that are resolved by trial is less than 5%! There are a few reasons why this is the case. First, trials are time-consuming and expensive. Second, you can never be absolutely sure what the result is going to be. You're always rolling the dice when you go to trial. Third, you can usually find a way to settle a dispute sooner than the first available trial date.

It also helps that the rules of court — both the Provincial Court Family Rules and the Supreme Court Family Rules — are written to promote settlement and find ways of pushing litigants toward the offramps that lead away from trial. (It says something, I think, that the rules of the province's two trial courts are designed to discourage trials.) This section talks about these offramps, the rules that are intended to encourage people to propose settlement options, the rules that provide judges to help people negotiate settlements, and the rules that penalize people for going to trial without fully thinking things through.

Introduction to rules promoting settlement

There are many reasons why it's important to resolve family law disputes other than by trial. From the court's point of view, when separated spouses or parents are able to reach a settlement of their legal problems, their agreement:

- helps to protect the children from their ongoing conflict

- frees up valuable judicial and administrative resources for other cases, and,

- decreases the likelihood that the dispute will require ongoing court hearings in the future.

From the point of view of the spouses or parents involved in the dispute, making an agreement:

- is cheaper and faster than going to trial,

- is more likely to give you more of what you want than a judicial decision,

- shows you and your ex that you can resolve even difficult disputes on your own, and

- resolves disputes and lets you move on with your life more quickly.

Settling a family law dispute gives spouses or parents a lot more personal control and creativity about the resolution of their dispute than is possible in court. It also gives everyone the best chance of being able to work together in the future.

(Lawyers also have an interest in settling matters, believe it or not, for all of the same reasons as the courts and the parties. As well, lawyers have a professional and an ethical duty to pursue settlement wherever possible, provided that a proposed settlement is not an unreasonable compromise of their clients' interests. This duty is so important that it has been written into lawyers' Code of Professional Conduct.)

The legislation on family law and the rules of court for family law proceedings have evolved over the last two or three decades to provide additional opportunities and incentives for settlement, and steer people out of court and away from trial whenever possible. In fact, the first division of Part 2 of the provincial Family Law Act is titled "Resolution Out of Court Preferred," and begins with a statement in section 4 which says that the purposes of the Part are to:

(b) to encourage parties to a family law dispute to resolve the dispute through agreements and appropriate family dispute resolution before making an application to a court;

(c) to encourage parents and guardians to

(i) resolve conflict other than through court intervention, and

(ii) create parenting arrangements and arrangements respecting contact with a child that is in the best interests of the child.

Under section 8(2), lawyers are required to "discuss with the party the advisability of using various types of family dispute resolution to resolve the matter." (That awful, clumsy term family dispute resolution is defined in section 1(1) as including mediation, arbitration, and collaborative negotiation.) Lawyers have the same sort of obligation under section 7.7 of the federal Divorce Act:

(2) It is also the duty of every legal adviser who undertakes to act on a person’s behalf in any proceeding under this Act

(a) to encourage the person to attempt to resolve the matters that may be the subject of an order under this Act through a family dispute resolution process, unless the circumstances of the case are of such a nature that it would clearly not be appropriate to do so;

(b) to inform the person of the family justice services known to the legal adviser that might assist the person

(i) in resolving the matters that may be the subject of an order under this Act, and

(ii) in complying with any order or decision made under this Act; and

(c) to inform the person of the parties’ duties under this Act.

Whether or not your lawyer gives you this encouragement or information, section 7.3 of the Divorce Act requires you, and the other parties to your court proceeding, to at least try to resolve your disagreements out of court:

To the extent that it is appropriate to do so, the parties to a proceeding shall try to resolve the matters that may be the subject of an order under this Act through a family dispute resolution process.

In general, you should try to resolve a court proceeding without going to trial if you can. However, your settlement, whether it's reached with the help of a judge or not, must be fair and reasonable and roughly within the range of what would have happened if the issues in your proceeding had been resolved at trial. While it's always a relief to wrap up a court proceeding, if the settlement is really unfair to either party a return to court may be inevitable!

The Provincial Court

In 2021, BC received a complete overhaul of its Provincial Court Family Rules. Visit Legal Aid BC's Family Law website for more guidance on what the new rules require you to do, and how this can change depending on where you are located. The purpose of the revamped Rules is aimed at promoting settlement, helping parties resolve their case by agreement, or to help them obtain a fair outcome in way that minimizes conflict and promotes cooperation between parties.

Section 8 of the Rules clearly states that “parties may come to an agreement or otherwise reach resolution about family issues at any time”. That means that even if it’s the morning of your trial and you’re all ready to go, you and your ex can decide to settle without going to trial.

The new Rules have also divided various courthouse registries into different categories. For example, Victoria is an Early Resolution Registry, Vancouver (Robson Square) is a Family Justice Registry, and Abbotsford is a Parenting Education Program Registry. For more information of each of these types of registry, see the section on Starting a Court Proceeding in a Family Matter, under the heading Early Resolution Registries.

No matter the registry in which you find yourself, there are certain steps you have to take before you’ll be able to argue before a judge. In most cases, the first time that parties will be before a judge will be at what’s called a Family Management Conference (also called an “FMC”), which is a settlement-focused appearance. If settlement isn’t possible at the FMC, the judge can make orders (by consent or not), make interim orders to address needs until resolution is reached, and determine next appropriate steps.

A notable difference between Supreme Court and Provincial Court is that costs are not payable in Provincial Court. That said, a word of caution: if a judge decides that cross examining an expert witness was unnecessary, then the party who decides to cross examine that expert can be responsible for the costs associated with that, which can be in the thousands of dollars.

The Supreme Court

The rules of the Supreme Court allow the court to refer people to other dispute resolution services, much like the rules of the Provincial Court. In addition to offering carrots like this, the Supreme Court Family Rules also include a stick or two. The biggest stick is the court's jurisdiction to make an order about costs. An order for "costs" is an order that one party pay for some or all of the expenses another party incurred dealing with the court proceeding. Costs are usually, but not always, awarded to the party who is most successful at trial. They can also be awarded to punish bad behaviour in the course of a court proceeding, or to penalize a party who failed to accept a reasonable settlement proposal.

Judicial case conferences

Rule 7-1 requires that the parties to a court proceeding attend a judicial case conference before they can send a Notice of Application or an affidavit to another party. This usually has the effect of making judicial case conferences a mandatory part of all family law cases in the Supreme Court. A judicial case conference, usually referred to as a "JCC," is a relatively informal, off-the-record, private meetings between the parties, their lawyers, and a master or judge in a courtroom.

Rule 7-1(15) gives the court a broad authority to take steps and make orders to promote the settlement of the court proceeding. Among other things, the master or judge may:

- identify the issues that are in dispute and those that are not in dispute and explore ways in which the issues in dispute may be resolved without recourse to trial;

- mediate any of the issues in dispute; and,

- without hearing witnesses, give a non-binding opinion on the probable outcome of a hearing or trial.

What's really cool about JCCs is that, under Rule 7-1(1), "a party may request a judicial case conference at any time, whether or not one or more judicial case conferences have already been held in the family law case." If there's a chance of settlement as you head toward trial, take advantage of this rule and book another JCC!

JCCs are discussed in more detail in the Case Conferences section of this chapter.

Settlement conferences

Settlement conferences are available under Rule 7-2 at the request of both parties. Settlement conferences are are relatively informal meetings between the parties, their lawyers, and a master or judge that are solely concerned with finding a way to settle the court proceeding.

Settlement conferences are private and are held in courtrooms that are closed to the public. Only the parties and their lawyers are allowed to attend the conference, unless the parties and the judge all agree that someone else can be present. They are held on a confidential, off-the-record basis, so that nothing said in the conference can be used against anyone later on.

Offers to settle

You can make a formal offer to settle at any time during a court proceeding. An "offer to settle" is a proposal about how all of the claims made in the claimant's Notice of Family Claim and in the respondent's Counterclaim will be wrapped up. A party receiving an offer to settle can decide to accept the offer or to refuse it. There are, however, important consequences for refusing a reasonable offer under Rule 11-1 that we'll talk about in a second.

It's important to know, first, that offers to settle are private and confidential. The point of this is to let someone make an offer to resolve a court proceeding without being held to that position if the offer is rejected and the case goes to trial. You want to be able to make a serious proposal that offers to compromise your position without being stuck with that compromise at trial. In fact, Rule 11-1 expressly states that no one can tell a judge that offer has been made until the case is wrapped up:

(2) The fact that an offer to settle has been made must not be disclosed to the court or jury, or set out in any document used in the family law case, until all issues in the family law case, other than costs, have been determined.

The stick shows up in subrules (5) and (6) when comparing the results of the trial against the terms of an offer to settle that was refused. These parts of Rule 11-1 say that:

(5) In a family law case in which an offer to settle has been made, the court may do one or more of the following:

(a) deprive a party of any or all of the costs, including any or all of the disbursements, to which the party would otherwise be entitled in respect of all or some of the steps taken in the family law case after the date of delivery or service of the offer to settle;

(b) award double costs of all or some of the steps taken in the family law case after the date of delivery or service of the offer to settle;

(c) award to a party, in respect of all or some of the steps taken in the family law case after the date of delivery or service of the offer to settle, costs to which the party would have been entitled had the offer not been made;

(d) if the party who made the offer obtained a judgment as favourable as, or more favourable than, the terms of the offer, award to the party the party's costs in respect of all or some of the steps taken in the family law case after the date of delivery or service of the offer to settle.

(6) In making an order under subrule (5), the court may consider the following:

(a) whether the offer to settle was one that ought reasonably to have been accepted, either on the date that the offer to settle was delivered or served or on any later date;

(b) the relationship between the terms of settlement offered and the final judgment of the court;

(c) the relative financial circumstances of the parties;

(d) any other factor the court considers appropriate.

Let's break this down a bit. What these subrules essentially say is that even if you were successful at trial, you may have to pay costs to the other side if their offer to settle was better than, or as good as, the result of the trial! The court may decide to:

- withhold an award of costs that you would normally be entitled to;

- make you pay some or all of the costs of the other side; and,

- make you pay double the normal costs of the other side after the date the offer was delivered to you.

Ouch. It pays to pay attention to an offer to settle.

To qualify as an offer to settle under Rule 11-1 an offer must:

- be in writing;

- be served on all parties to the court proceeding; and,

- include this sentence

"The [Claimant or Respondent], [name of party], reserves the right to bring this offer to the attention of the court for consideration in relation to costs after the court has pronounced judgment on all other issues in this proceeding."

An offer to settle must meet these requirements if the party making the offer is going to ask the court for a costs order under Rule 11-1(5).

Costs

In the Supreme Court, a party may ask for their costs of an application, of a trial or of the whole of a court proceeding under Rule 16-1. "Costs" are a partial payment of the expenses and legal fees incurred by a party to a court proceeding, and are calculated under a schedule included in the Supreme Court Family Rules. Costs normally don't amount to more than approximately 30% of a party’s actual legal fees.

Normally, the party who gets most of what they asked gets an order that the other side pay their "costs," but there are exceptions. In general, costs are a sort of idiot tax designed to punish a litigant who has unreasonably started or defended a court proceeding. Say, for example, you were hit by a car and you sue the driver for $10,000. Here are some possible outcomes and how costs might work if the driver refuses to pay and defends your claim.

- You are successful at trial and get an award of $10,000. You would get your costs because the driver was an idiot for refusing to pay the money you asked for and making both of you go through a trial.

- You are successful at trial and get an award of $1,000. Even though you were successful, the driver would probably get their costs because you had demanded an unreasonable amount and the driver was right to defend your claim. You were an idiot for asking for too high an amount of money, which forced the driver to go through a trial.

- You are unsuccessful at trial. The driver would get their costs because you were an idiot for suing the driver in the first place. Your unreasonable behaviour forced the driver to go through a trial.

The schedule that is used to calculate the amount of costs payable is in Appendix B of the Supreme Court Family Rules. Under that schedule, you get a specific amount of money for specific steps taken in a court proceeding. The amount you get varies depending on whether the court proceeding was of less than ordinary difficulty, of ordinary difficulty, or of more than ordinary difficulty. "Ordinary difficulty" is the default if the court that makes a costs order makes no order about the difficulty of the court proceeding. Here's the list of those steps and the amounts payable depending on difficulty:

In addition to costs calculated under the schedule, a party who gets their costs also usually gets reimbursed for the money they spent on reasonable and necessary disbursements as well. Disbursements are out-of-pocket expenses for things like court filing fees, witness fees, transcripts, experts’ fees, photocopies, couriers, postage, and the like.

The likelihood of a cost award being made after a hearing or trial can provide a strong incentive for people to try and settle their court proceeding. It can encourage parties to be more reasonable in their positions and try to reduce the number of issues that need court intervention.

For more information about costs, see the Legal Services Society's Family Law website's information page If you have to go to court under the section "Costs and expenses."

The Notice to Mediate Regulation

Under the Notice to Mediate (Family) Regulation, someone who is a party to a court proceeding in the Supreme Court can make the other parties go to mediation by serving a Notice to Mediate on them.

A Notice to Mediate must be served at least 90 days after the Response to Family Claim is filed but at least 90 days before the scheduled trial date. Once the Notice is served, the parties must attend mediation unless:

- a party has triggered a mediation meeting using a Notice to Mediate;

- there is a protection order against a party;

- the mediator decides that the mediation is not appropriate or will not be productive; or,

- the court orders that a party is exempt because, in the court’s opinion, it is "impracticable or materially unfair" to require the party to attend.

The Notice to Mediate (Family) Regulation provides the guidelines for proceeding with the mediation. In a nutshell:

- the parties must jointly appoint a mediator within 14 days after service of the Notice to Mediate, and if they can't agree on a mediator, any of them may apply to a roster organization for the appointment of a mediator;

- the mediator must have a pre-mediation meeting with each party to screen for power imbalances and family violence, and talk about preparing for the mediation;

- the parties sign the mediator's participation agreement; and,

- the parties attend a mediation meeting, which concludes when the legal issues are resolved or when "the mediation session is completed and there is no agreement to continue."

It seems unlikely that a mediation that people are forced to attend could produce a settlement. However, even compulsory mediation sometimes works. While no one is going to be happy being compelled to do something they'd rather avoid, if the process results in a settlement, it's probably worth it. The time and money spent on the mediation process will be a fraction of the time and money you'll spend on trial.

Resources and links

Legislation

- Provincial Court Family Rules

- Provincial Court Act

- Supreme Court Family Rules

- Supreme Court Act

- Court of Appeal Rules

- Court of Appeal Act

- Court Rules Act

Resources

- Provincial Court Practice Directions

- Supreme Court Family Practice Directions

- Supreme Court Administrative Notices

- Court of Appeal Practice Directives

- Tug of War by Mr. Justice Brownstone

- "The Rights and Responsibilities of the Self-Represented Litigant" (PDF) by John-Paul Boyd

Links

- Legal Aid BC's Family Law website information on Provincial Court process:

- Courts of British Columbia website

- Provincial Court website

- Supreme Court website

- Supreme Court Trial Scheduling

- Court of Appeal website

- Guidebooks from the BC Supreme Court website

- Justice Education Society's Court Tips for Parents (videos)

| This information applies to British Columbia, Canada. Last reviewed for legal accuracy by JP Boyd, 3 April 2020. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||