Recent Changes to Family Law in British Columbia

Family law has changed a lot over the past 15 years or so, especially if you live in British Columbia. In 2010, special Supreme Court rules, just for family law cases, were introduced. In 2013, the Family Law Act replaced the Family Relations Act and brought in new ways of thinking about parenting after separation, a new test that applies when someone wants to move away after separation, a new scheme for dividing property between spouses, new provisions about parenting coordination, and new tools to help judges to manage court processes. In 2019, the Provincial Court established a pilot project in the Victoria courthouse aimed at the early resolution of family law disputes, complete with a whole new set of court rules just for the pilot project. In 2020, the Family Law Act was changed to cover the arbitration of family law disputes, in terms very different from those of the old Arbitration Act, and the Victoria pilot project was expanded to include the Surrey courthouse. Of course, 2020 was also the year that the spread of COVID-19 resulted in huge changes to day-to-day court processes.

In 2021, sweeping amendments to the federal Divorce Act came into effect that changed how we talk about parenting after separation, and introduced a new test for figuring out children's best interests and a new test for when someone wants to move away. Thankfully, for people already used to the Family Law Act, the changes to the Divorce Act felt very familiar, as if the federal government had simply copied huge swathes from our legislation. However, the changes to the Divorce Act also resulted in changes to the Child Support Guidelines, changes to the forms used by the Supreme Court, and the introduction of brand new forms used when someone wants to move away or objects to someone moving away.

Frankly, the pace of change has been a bit dizzying, especially for those of us who prepare public and professional education materials on family law. However, these changes are all part of an important new trend in family law to encourage people to resolve their problems outside of court, to recognize and account for the important impacts of family violence and coercive, controlling relationships, and to focus the rights involved in parenting more on children than on parents. The inconvenience to public legal educators is worth it.

Introduction

The key changes to the federal Divorce Act are discussed in the page on the new Divorce Act. The Family Law Act Basics page provides a fairly thorough outline of the Family Law Act in a helpful question and answer format, and you can get a good overview of how family law works in British Columbia in the page on the Legal System.

This page provides an overview of the other changes that have happened in the last couple of years, including the amendments to the Family Law Act about arbitration, the new Provincial Court pilot project, and the changes to the Child Support Guidelines and the forms used by the Supreme Court resulting from the amendment of the Divorce Act.

Arbitration under the Family Law Act

Until 1 September 2020, all you needed to know about the arbitration of family law disputes could be found in the provincial Arbitration Act. That law, which used to be called the Commercial Arbitration Act, was an all-purpose piece of legislation meant to apply to the arbitration of almost every kind of legal dispute from car accidents to construction defects. However, when the provincial government began to think about retooling that legislation it also began to think about creating a spot in the Family Law Act just for arbitration.

This made a lot of sense, as one of the important changes the Family Law Act introduced in 2013 was to encourage people to resolve their family law disputes other than through court. Section 4 of the act said it was important for people to learn about all of the different ways to resolve family law disputes, section 5 imposed a duty on people to give each other full and complete disclosure whether they were resolving their dispute in court or not, and section 8 required lawyers to assess for the presence of family violence and advise their clients about the different options for resolving their dispute in light of that assessment. Sections 10 to 13 talked about the services Family Justice Counsellors provide to help people resolve their disagreements, and sections 14 to 19 allowed the court to appoint parenting coordinators, making British Columbia the first jurisdiction in Canada to provide for parenting coordination in its legislation. Why not fold arbitration into the Family Law Act too?

That's what sections 19.1 to 19.22 do, and section 2(5)(b) of the new Arbitration Act makes it clear that the arbitration of family law disputes is now governed solely by the Family Law Act.

(If you're wondering why the new sections of the Family Law Act are numbered 19.1, 19.2, 19.3 and so on instead of 20, 21 and 22, it's because of the havoc that would be created if the entire Family Law Act were renumbered when new parts are added or taken out. Think about all the cases that talked about the old section 21 that wouldn't make sense anymore! Instead, new sections that need to be inserted are given a new series of numbers after a decimal point. This way, if you added two sections between sections 68 and 69, the sections would be numbered as 68, 68.1, 68.2, 69, 70 and so on, and the cases that talk about sections 69 and 70 still talk about the same sections 69 and 70. The same thing applies to inserting new bits into an existing section. To add a new subsection between (c) and (d), for example, the subsection would be numbered (c.1), and the subsections would be numbered as (a), (b), (c), (c.1), (d) and (e). It's confusing to read, but it's a good solution.)

Here are the highlights of the new parts of the Family Law Act on arbitration.

Agreements to arbitrate: Under section 19.2, people can make an agreement to resolve a family law problem by arbitration, including future family law problems. These agreements can specify who the arbitrator will be, say how the arbitrator will make decisions, say what processes will be used in the arbitration, and say how evidence will be handled.

Cancelling agreements to arbitrate: Under section 19.3, however, the court can cancel an arbitration agreement if one party took advantage of another party in getting them to sign the agreement, one of the parties didn't understand the meaning or effect of the agreement, or there is a problem with the agreement under the law of contracts.

Effect of agreements to arbitrate: If you have an agreement to arbitrate and the other party tries to go to court instead, under section 19.4 you can ask the court to stop the court case.

Appointing the arbitrator: Under section 19.6, if you can't agree on who should arbitrator your family law problem, the court can appoint one for you. However, once an arbitrator has been appointed, whether by your agreement or a court order, the arbitrator can't be fired by just one party. Under section 19.7, everyone involved in the disagreement has to agree to fire the arbitrator.

Role of the arbitrator: Section 19.8 says that an arbitrator must be independent of the parties and impartial. Someone who is asked to serve as an arbitrator must explain any reasons why they might not be able to be independent and impartial, and this duty continues throughout the arbitration process. The court can remove someone as arbitrator under section 19.9 if there are reasonable doubts about the arbitrator's independence and impartiality.

Choice of law: Under section 19.10, you get to choose the law that applies to your disagreement! You can decide, for example, that the arbitrator will apply the law of British Columbia or the law of some other place, or decide the problem based on fairness and equity.

Evidence: If section 19.10 wasn't cool enough, under section 19.11 the arbitrator has the power to decide how evidence is handled and isn't required to apply the rules of evidence that normally apply in court. This means that the arbitrator can decide to let the parties present evidence that they wouldn't necessarily be able to present in court. Under section 19.12, the arbitrator can also compel other people to provide evidence in an arbitrator.

Awards: Under section 19.14, the arbitrator's decision, called an award, must be in writing, signed and given to the parties. Once the parties have the award, under section 19.15, they have no more than 30 days to ask the arbitrator to correct any errors or explain a part of their award. Awards are binding on the parties under section 19.16.

Challenging awards: Awards can be appealed under section 19.19, which says that the parties have no more than 30 days after getting the arbitrator's award to start an appeal. You can also ask the court to cancel an award under section 19.18, if the arbitrator wasn't independent or impartial, if a party wasn't given the opportunity to be heard during the arbitration, if the award was improperly obtained, or if the arbitrator made decisions about issues that weren't in the arbitration agreement.

Enforcing awards: Awards are binding on the parties to arn arbitration under section 19.16. Under section 19.20, awards can be filed in court and be enforced by the court as if they were court orders.

Changes to the Child Support Guidelines

Don't worry, none of the really important parts of the Child Support Guidelines have changed. The only changes that have been made update the Guidelines to use the new terminology used by the Divorce Act.

Split custody: Split custody under section 8 of the Guidelines is now called "split parenting time." Parents have split parenting time when each of the parents has the primary home of one or more of their children.

Shared custody: Shared custody under section 9 of the Guidelines is now called "shared parenting time." Parents have shared parenting time when the children live with each of them for 40% or more of the time.

New and Revised Supreme Court Forms

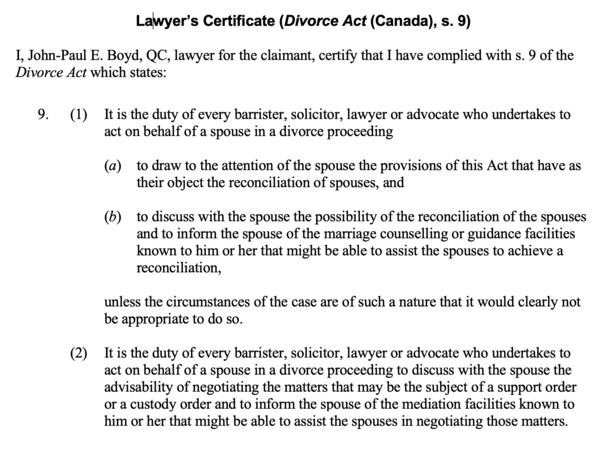

Under the old Supreme Court forms used to make claims in family law disputes, the Notice of Family Claim and the Counterclaim, lawyers had to "certify" that they have complied with their duties under the Divorce Act. "Certify" isn't as fancy as it sounds. Basically, lawyers put the date and their signature below a part of the form that looked like this:

Lawyers' duties are basically the same under the new Divorce Act, but they're now found in section 7.7. The big change for the people asking for a divorce is the new duties they have under sections 7.1 to 7.5 of the Divorce Act. Among other things, these sections say that:

- people have to exercise entitlements to parenting time, decision-making responsibility and contact in a way that is consistent with the best interests of the child,

- parties must protect the children from the conflict arising from their court case,

- parties have to try to resolve their disagreements out of court if possible, and

- parties have to give each complete, accurate and up-to-date information as necessary to resolve their disagreement.

Under the new section 7.6, the parties to a course case under the Divorce Act have to certify that they are "aware" of these duties, and need to sign a certificate in their Notice of Family Claim or Counterclaim just like lawyers do.

There's also a form that's brand new, Form F102, Statement of Information for Corollary Relief Proceedings. Corollary relief refers to claims made about parenting after separation, child support or spousal support under the Divorce Act, but this form is only needed when someone is asking for orders about parenting after separation. The form requires you to describe any:

- civil protection orders or cases about your spouse, yourself or your children,

- child protection orders or cases about your children, and

- criminal cases about your spouse or yourself, the nature of the charges, and any orders, peace bonds or undertakings that have been made.

This form is necessary, because under section 7.8 of the new Divorce Act, judges must take into account cases like these, and any orders made in those cases, when making decisions about parenting after separation.

The Provincial Court Pilot Project

Resources and links

Legislation

- the old Divorce Act

- Bill C-78

Links

- An Overview of Bill C-78 by John-Paul Boyd

| This information applies to British Columbia, Canada. Last reviewed for legal accuracy by JP Boyd, February 15, 2021. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||